IN MID-APRIL, an arsenal of powerful software tools apparently designed by the NSA to infect and control Windows computers was leaked by an entity known only as the “Shadow Brokers.” Not even a whole month later, the hypothetical threat that criminals would use the tools against the general public has become real, and tens of thousands of computers worldwide are now crippled by an unknown party demanding ransom.

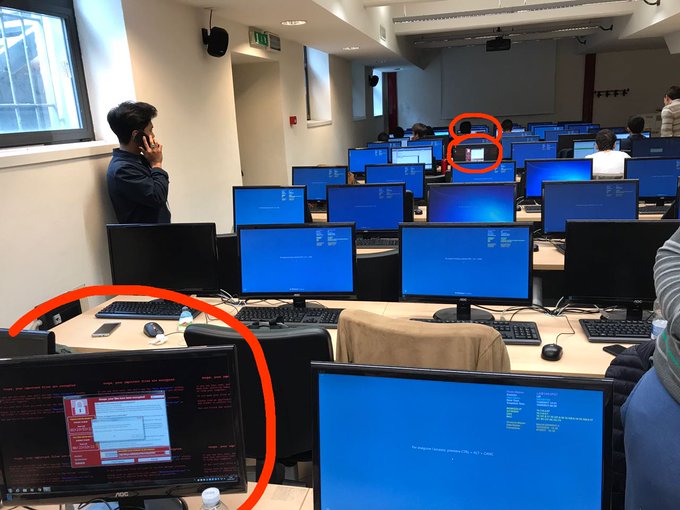

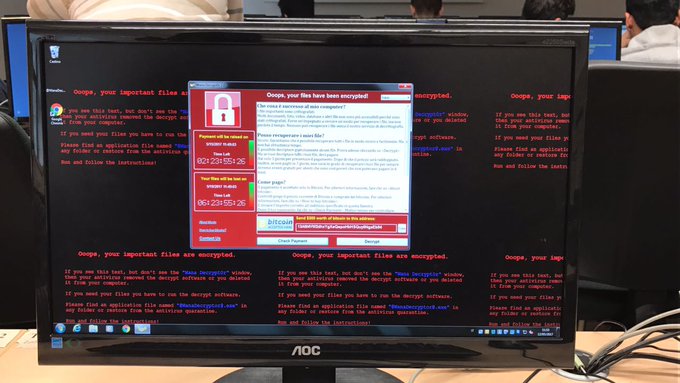

The malware worm taking over the computers goes by the names “WannaCry” or “Wanna Decryptor.” It spreads from machine to machine silently and remains invisible to users until it unveils itself as so-called ransomware, telling users that all their files have been encrypted with a key known only to the attacker and that they will be locked out until they pay $300 to an anonymous party using the cryptocurrency Bitcoin. At this point, one’s computer would be rendered useless for anything other than paying said ransom. The price rises to $600 after a few days; after seven days, if no ransom is paid, the hacker (or hackers) will make the data permanently inaccessible (WannaCry victims will have a handy countdown clock to see exactly how much time they have left).

Ransomware is not new; for victims, such an attack is normally a colossal headache. But today’s vicious outbreak has spread ransomware on a massive scale, hitting not just home computers but reportedly health care, communications infrastructure, logistics, and government entities.

Reuters said that “hospitals across England reported the cyberattack was causing huge problems to their services and the public in areas affected were being advised to only seek medical care for emergencies,” and that “the attack had affected X-ray imaging systems, pathology test results, phone systems and patient administration systems.”

The worm has also reportedly reached universities, a major Spanish telecom, FedEx, and the Russian Interior Ministr In total, researchers have detected WannaCry infections in over 57,000 computers across over 70 countries (and counting — these things move extremely quickly).

According to experts tracking and analyzing the worm and its spread, this could be one of the worst-ever recorded attacks of its kind. The security researcher who tweets and blogs as MalwareTech told The Intercept, “I’ve never seen anything like this with ransomware,” and “the last worm of this degree I can remember is Conficker.” Conficker was a notorious Windows worm first spotted in 2008; it went on to infect over 9 million computers in nearly 200 countries.

Most importantly, unlike previous massively replicating computer worms and ransomware infections, today’s ongoing WannaCry attack appears to be based on an attack developed by the NSA, code-named ETERNALBLUE. The U.S. software weapon would have allowed the spy agency’s hackers to break into potentially millions of Windows computers by exploiting a flaw in how certain versions of Windows implemented a network protocol commonly used to share files and to print. Even though Microsoft fixed the ETERNALBLUE vulnerability in a March software update, the safety provided there relied on computer users keeping their systems current with the most recent updates. Clearly, as has always been the case, many people (including in government) are not installing updates. Before, there would have been some solace in knowing that only enemies of the NSA would have to fear having ETERNALBLUE used against them — but from the moment the agency lost control of its own exploit last summer, there’s been no such assurance. Today shows exactly what’s at stake when government hackers can’t keep their virtual weapons locked up. As security researcher Matthew Hickey, who tracked the leaked NSA tools last month, put it, “I am actually surprised that a weaponized malware of this nature didn’t spread sooner.”

The infection will surely reignite arguments over what’s known as the Vulnerabilities Equity Process, the decision-making procedure used to decide whether the NSA should use a security weakness it discovers (or creates) for itself and keep it secret, or share it with the affected companies so that they can protect their customers. Christopher Parsons, a researcher at the University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab, told The Intercept plainly: “Today’s ransomware attack is being made possible because of past work undertaken by the NSA,” and that “ideally it would lead to more disclosures that would improve the security of devices globally.”

But even if the NSA were more willing to divulge its exploits rather than hoarding them, we’d still be facing the problem that too many people really don’t seem to care about updating their software. “Malicious actors exploit years old vulnerabilities on a routine basis when undertaking their operations,” Parsons pointed out. “There’s no reason that more aggressive disclose of vulnerabilities through the VEP would change such activities.”

A Microsoft spokesperson provided the following comment:

Today our engineers added detection and protection against new malicious software known as Ransom:Win32.WannaCrypt. In March, we provided a security update which provides additional protections against this potential attack. Those who are running our free antivirus software and have Windows updates enabled, are protected. We are working with customers to provide additional assistance.

Comments

Post a Comment